Drivers and Predictability of Antarctic Sea Ice Extremes - A machine learning approach

Doctoral Researcher:

Nina Öhlckers, AWI and University of Bremen, nina.oehlckers@awi.de

Supervisors:

- Dr. Monica Ionita, AWI

- Prof. Dirk Lorenz, University of Bremen

- Prof. Gerrit Lohmann, AWI

Location: Bremerhaven

Disciplines: Data science, Antarctic Sea Ice, Statistical Modelling

Keywords: Sea Ice Forecasting, Sea Ice Reconstruction, Teleconnections, Data Analysis, Atmosphere

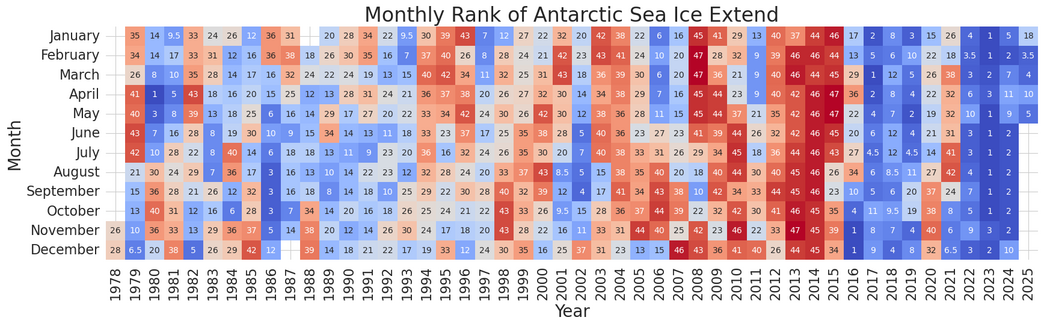

Motivation: In contrast to the Arctic sea ice as well as earth system model forecasts, Antarctic sea ice had shown a positive decadal trend since the start of satellite records from 1978 until 2015, with strong regional differences. However, in recent years since 2015, ASI has rapidly declined, breaking historic minima records [21]. A monthly rank map in 1 shows the development since the start of the satellite era with red indicating a larger sea ice extend and blue a smaller sea ice extend in the whole of Antarctica. The driving forces that caused this development remain controversial, with some scientists already claiming an overall regime shift [21].

Sea ice dynamics are influenced by a complex web of interconnected atmospheric and oceanic factors that change both spatially and over time. As the entire climate system is connected in the attempt to compensate radiation

imbalance by transferring energy from low to high latitudes [3], all climate events are connected and events in one area of the world can cause events in other areas. Understanding these connections is crucial in order to perform accurate weather and climate predictions. However, despite a lot of research revealing different climate factors that influence ASI in different regions, such as atmospheric rivers [12], [11], [23], El Ni˜no-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [22], [14], [2], Southern Annular Mode (SAM) [2], [13], Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) [4] and polar cyclones [10], there is no consensus on global patterns that cause extreme events of ASI [7].

Due to the remoteness of Antarctica, there are only very few in-situ observations, making models dependent on satellite data. However, consistent sea ice concentration datasets only reach back to 1978, when the first microwave satellite mission with the Nimbus-7 SMMR sensor (NSIDC) was launched. In order to better understand long-term trends and developments, as well as detect if recent changes are a regime shift, or due to natural variability, reliable sea ice reconstructions are required. While reconstructions based on statistical methods [9], [18] and data inferred climatological estimation [5] have been introduced, so far the use of ML models to improve ASI reconstructions has not been explored.

Predicting sea ice concentration and extend is crucial to understand and forecast ecosystem changes and cascading effects, such as ice sheet melt and sea level rise. Commonly used numerical earth-system-models, such as CMIP6, fail to capture recent ASI trends, most likely due to insufficient representation of atmosphere-ocean-ice interactions and processes [8]. Utilizing ML methods can overcome this problem and uncover nonlinear relationships between various data types, advancing prediction accuracy. While many ML models have already been developed to predict Arctic sea ice behaviour, model development for the Antarctic has only recently gained momentum, eg. [17], [16], [15], [19]. Models are still sparse and often reduced to local input data, ignoring global drivers and physics. The integration of machine learning with traditional modeling holds immense promise for understanding ASI’s complex dynamics [20].

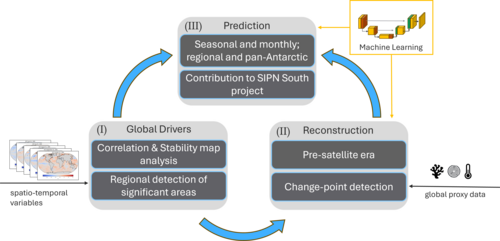

Aim: The aim of the PhD is to detect underlying global drivers that cause ASI variability and can act as predictors to improve seasonal to monthly forecasts. By utilizing correlation and causality analysis methods, such as, but not limited to, stability maps [1] and Granger causality tests, possible relationships between global teleconnection patterns and sea ice variability can be uncovered. These relationships can enhance understanding of global relationships and be used as input to machine learning models for sea ice prediction, such as Transformers. Further more, proxy data from detected influential areas can be used to generate informed ASI reconstructions, which in turn can also improve predictions.

After successful development of a seasonal prediction model, participation in the SIPN South project is aspired.

Objective: The objective of the PhD is to i) unravel key drivers and feedback mechanisms responsible for ASI extremes,

revealing potentially overlooked mechanisms and regional dependencies, ii) create a reconstructional dataset of

ASI and iii) develop a new ML based method to advance the monthly to seasonal ASI prediction, as shown in 2.

The PhD aims to contribute insights to the broader research community that allow to uncover cascading effects

resulting in sea level rise, changes in ocean dynamics and the palegic foodweb.

References:

[1] Monica Ionita, Gerrit Lohmann, and Norel Rimbu. “Prediction of Spring Elbe Discharge Based on Stable Teleconnections with Winter Global Temperature and Precipitation”. EN. In: Journal of Climate 21.23 (Dec. 2008). Publisher: American Meteorological Society Section: Journal of Climate, pp. 6215–6226.

[2] S. E. Stammerjohn et al. “Trends in Antarctic annual sea ice retreat and advance and their relation to El Ni˜no–Southern Oscillation and Southern Annular Mode variability”. en. In: Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 113.C3 (2008).

[3] William Ruddiman. Earth’s Climate: Past and Future. Englisch. 3rd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman, Oct. 2013.

[4] Xichen Li et al. “Impacts of the north and tropical Atlantic Ocean on the Antarctic Peninsula and sea ice”. en. In: Nature 505.7484 (Jan. 2014).

[5] Holly A. Titchner and Nick A. Rayner. “The Met Office Hadley Centre sea ice and sea surface temperaturedata set, version 2: 1. Sea ice concentrations: HADISST.2.1.0.0 SEA ICE CONCENTRATIONS”. en. In: Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 119.6 (Mar. 2014), pp. 2864–2889.

[6] Fetterer, F.; Knowles K.; Meier W.; Savoie M.; Windnagel A. Sea Ice Index, Version 3. en. 2017.

[7] Edward Blanchard-Wrigglesworth et al. “Impact of Winds and Southern Ocean SSTs on Antarctic Sea Ice Trends and Variability”. en. In: (Feb. 2021). Section: Journal of Climate.

[8] Xavier Crosta et al. “Antarctic sea ice over the past 130 000 years – Part 1: a review of what proxy records tell us”. English. In: Climate of the Past 18.8 (Aug. 2022). Publisher: Copernicus GmbH, pp. 1729–1756.

[9] Ryan L. Fogt et al. “A regime shift in seasonal total Antarctic sea ice extent in the twentieth century”. en. In: Nature Climate Change 12.1 (Jan. 2022).

[10] B. Jena et al. “Record low sea ice extent in the Weddell Sea, Antarctica in April/May 2019 driven by intense and explosive polar cyclones”. en. In: npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 5.1 (Mar. 2022).

[11] Irina V. Gorodetskaya et al. “Record-high Antarctic Peninsula temperatures and surface melt in February 2022: a compound event with an intense atmospheric river”. en. In: npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 6.1 (Dec. 2023).

[12] Kaixin Liang et al. “The Role of Atmospheric Rivers in Antarctic Sea Ice Variations”. en. In: Geophysical Research Letters 50.8 (2023).

[13] Serena Schroeter, Terence J. O’Kane, and Paul A. Sandery. “Antarctic sea ice regime shift associated with decreasing zonal symmetry in the Southern Annular Mode”. English. In: The Cryosphere 17.2 (Feb. 2023).

[14] M. Swathi, Avinash Kumar, and Rahul Mohan. “Spatiotemporal evolution of sea ice and its teleconnections with large-scale climate indices over Antarctica”. In: Marine Pollution Bulletin 188 (Mar. 2023), p. 114634.

[15] Yunhe Wang et al. “Subseasonal Prediction of Regional Antarctic Sea Ice by a Deep Learning Model”. en. In: 50.17 (2023).

[16] Xiaoran Dong et al. “Antarctic sea ice prediction with A convolutional long short-term memory network”. In: Ocean Modelling 190 (Aug. 2024), p. 102386.

[17] Xiaoran Dong et al. “Deep Learning Shows Promise for Seasonal Prediction of Antarctic Sea Ice in a Rapid Decline Scenario”. en. In: Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 41.8 (Aug. 2024), pp. 1569–1573.

[18] T. J. Maierhofer et al. “A Bayesian Model for 20th Century Antarctic Sea Ice Extent Reconstruction”. en. In:Earth and Space Science 11.10 (2024).

[19] Ziying Yang et al. “Extended seasonal prediction of Antarctic sea ice using ANTSIC-UNet”. English. In: EGUsphere (June 2024).

[20] Jianxin He et al. “Physically Constrained Spatiotemporal Deep Learning Model for Fine-Scale, Long-Term Arctic Sea Ice Concentration Prediction”. In: IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 63 (2025)

[21] Marilyn N. Raphael et al. “A twenty-first century structural change in Antarctica’s sea ice system”. en. In: Communications Earth & Environment 6.1 (Feb. 2025). Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, pp. 1–9.

[22] Shaoyin Wang et al. “Strong impact of the rare three-year La Ni˜na event on Antarctic surface climate changes in 2021–2023”. en. In: npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 8.1 (May 2025).

[23] Jonathan D. Wille et al. “Atmospheric rivers in Antarctica”. en. In: Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 6.3 (Mar. 2025).